A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens to Blow Up Obamacare

Telemarketers are selling cheap plans so bare-bones they’d normally be illegal. They’re doing it by signing people up for fake jobs.

Joe Strohmenger, a self-employed contractor in Rocky Point, New York, had never shopped for health insurance before. So last year, when he needed to, he did what a lot of people do: He Googled it.

The internet search led him to a website that offered free quotes. He typed in his number, and his phone rang immediately. It rang hundreds of times over the next few days as telemarketers vied to reach him.

Health-Care Hustlers

This story is the first in a series about the shady side of health-care telemarketing.

The plan Strohmenger and his wife, Sarah, ended up buying from one of those salesmen sounded like normal health insurance, they say. They got the impression that it covered all the basics, including hospitalization and emergency-room visits. The telemarketer even promised, they say, that it would cover the pricey specialist monitoring Joe’s benign brain tumor.

But after paying $8,734 for a year’s coverage, the Strohmengers learned the plan didn’t include those things. In fact, it was so bare-bones that selling it in the US would normally be illegal.

Only months later did the Strohmengers learn how the salesman pulled it off. At the time he enrolled them in the health plan, he also signed up Joe for a fake job at a tech company in Georgia. Joe says he was never told about the job, never got paid and never did any work. But the bogus relationship opened a loophole that the salesman used to sidestep most insurance laws.

Without meaningful coverage, the Strohmengers started avoiding medical care. Joe, who’s 40, skipped visits to the tumor doctor. Sarah, 39, tried and failed to get a refund. When they contacted the New York state insurance regulators, they said they were unable to help.

“How can someone take this much money from us and no one do anything about it?” says Sarah Strohmenger, who runs a skin-care boutique near her home on the north shore of Long Island. “Why is no one regulating this?”

The Strohmengers are among more than 100,000 US households that have bought plans tied to fake jobs in recent years, data compiled by Bloomberg News show. And their experience echoes complaints from hundreds of consumers across the country, according to a review of government records and interviews with customers, salespeople and regulators. But because the plans are backed by obscure companies with names like Socios Buenos and Vitamin Patch, not by insurance carriers, it’s unclear who, if anyone, has the authority to regulate them.

Some Republican officials have endorsed the legal theory behind the plans, seeing it as a way to deregulate the US health-insurance system without congressional action. That theory is the subject of a long-running dispute in a federal court in Texas that may be resolved in the coming months. Favorable action by the Trump administration or a judge could bring the plans to millions more customers and reshape health insurance in America. It might also make a fortune for the former TV comedy writer behind it all.

“We thought we could just contact someone and buy insurance”

“We thought we could just contact someone and buy insurance”

“We thought we could just contact someone and buy insurance”

The flurry of calls bombarding Joe’s phone was the first sign the Strohmengers had stumbled into a sketchy corner of the health-care industry. They hadn’t expected it to be this way. Joe was looking for insurance after he gave up his union plan to start a small business installing tile and renovating bathrooms. “This was all new,” Joe says. “We thought we could just contact someone and buy insurance.”

But if you look for health insurance on the internet, you might end up talking to a telemarketer offering a cheap product that, in the end, doesn’t provide much coverage. Policy experts call it “junk insurance.”

The heart of the industry is South Florida, where hundreds of call centers clutter the boulevards and office parks around Fort Lauderdale. Even though junk policies are cheaper than plans sold under the Affordable Care Act, the 2010 law known as Obamacare, they pay bigger commissions, making them more profitable to sell and leaving less money to fund claims. Fast-talking salespeople have been known to use fake names, pose as government workers and pretend plans are backed by Aetna Inc. or Blue Cross & Blue Shield. Top earners flaunt gold chains and Lamborghinis on Instagram. The products they sell are varied. Fake-job plans are the newest addition to the lineup.

Not long after the calls started coming in, Joe heard a pitch that sounded promising, so he set the phone on the kitchen table, allowing Sarah to join in. On speaker was a 24-year-old salesman named Tylor Trego. His agency, Quick Health, was located near Reading, Pennsylvania, but the setup wouldn’t have been out of place in Florida: a noisy room crammed with about 40 desks and phones, with salespeople pushing cheap, low-benefit plans.

Although Quick Health had been in business only a few years, it had already been banned in four states for using deceptive sales scripts, selling without a license, lying about coverage and committing other offenses. It had even attracted the attention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which searched the place in 2022 alongside state insurance officials, seizing computers and questioning employees. No criminal charges have been publicly filed, and the FBI declined to comment.

The Strohmengers weren’t aware of any of that. On the phone, the salesman sounded friendly. He told them he’d researched a wide range of options and identified the best plan, Joe recalls. He assured them it would pay for visits to the specialist monitoring Joe’s tumor, as well as his $1,500-a-month prescription for a drug to lower his blood sugar, Joe says. The plan wasn’t as expensive as they had feared, and the agent told them they could save more by paying for a full year up front.

“It covered everything we needed, and we’re like, OK, this isn’t that bad,” Sarah says, cradling a cup of coffee in her two-bedroom home. “It’s embarrassing how stupid we were.”

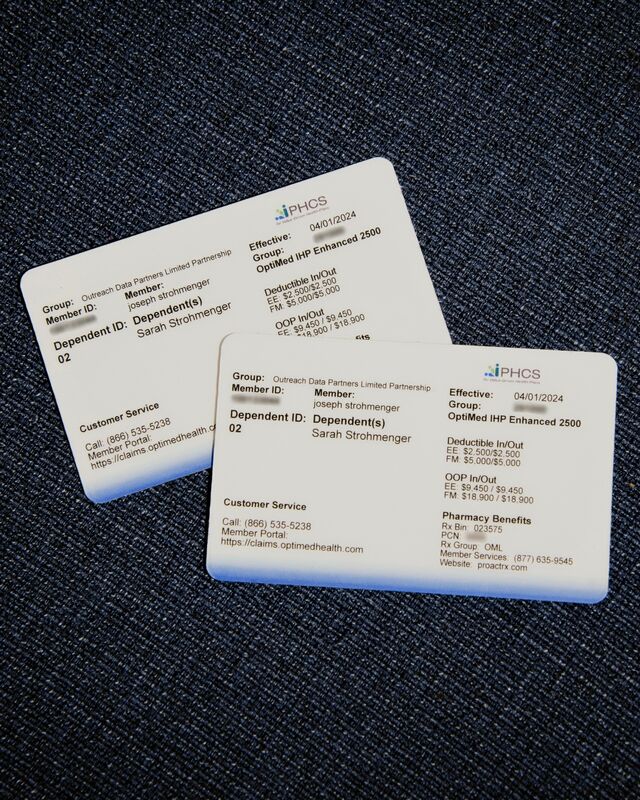

Soon, a pair of white plastic ID cards arrived in the mail. The cards didn’t show the name of any insurance company, but they indicated Joe was a “member” of something called Outreach Data Partners LP.

If the Strohmengers had tried to check out their new insurance provider, they probably wouldn’t have learned much. Outreach didn’t have a public-facing website. It reported 4,800 employees in a government filing, but LinkedIn didn’t list a single one. Its headquarters was Box 371 at a UPS store in a strip mall in Atlanta, sandwiched between a dry cleaner and a Vietnamese restaurant.

The Strohmengers didn’t examine the cards too closely. The salesman said the coverage was good, so what did it matter?

It mattered. Under Obamacare, health insurance plans sold on the market must cover 10 “essential health benefits,” including prescription drugs, emergency-room visits and hospitalization. Employee plans provided by large companies don’t have to meet those standards, although most do voluntarily.

Outreach is one of a new breed of companies set up to exploit that gap. By conjuring an employment relationship, however tenuous, with strangers on the telephone, it can sell them plans with far skimpier coverage than required in the Obamacare marketplace.

Here’s how it works: At the same time they buy a health plan from a company like Outreach, customers sign papers agreeing to become limited partners and contribute some work. That’s enough, these companies contend, to establish an employee relationship under the federal benefits law known as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, or Erisa. (Joe says he signed some documents electronically without fully reading them during the phone call with the salesman. He says he wasn’t provided with a copy afterward.)

The “work” typically involves installing an app on their phones, such as a web browser alternative to Apple’s Safari or Google Chrome. The data company harvests information from the app and, theoretically, sells it to advertisers looking for insights on consumer habits. Promoters of the scheme argue that the setup creates an employee relationship, even if the data generates little or no profit.

Not long after the ID cards arrived, the Strohmengers’ pharmacy said the plan wouldn’t pay for Joe’s medication after all. Then his doctor’s office said visits weren’t covered, either.

So Joe called Quick Health. This time, he got routed to a different salesman, who told him a more expensive version of the plan would cover everything, he says. After a bewildering series of transactions — including a refund that was deposited in their bank account and then retracted — the couple ended up having paid for two policies, plus an extra $1,500 whose purpose was never explained, he says. Now they were out about $20,000, and the new plan didn’t meet their needs any better than the old one.

Sarah spent hours last summer trying to get at least something back. Text messages and emails show Quick Health employees promising that as much as $12,000 was on the way, but some technical glitch always cropped up. “This is our hard earned saved money,” she texted one employee. “It’s disgusting what you are doing to us.”

Quick Health Chief Executive Officer Arthur Walsh and two of his lieutenants blame Outreach for some of the Strohmengers’ problems. In an interview at the call center, in a commercial building next to a freeway, they say that the data company failed to pay some valid claims. They say the salesmen never misled anyone about coverage, and that one of the refund mix-ups was the Strohmengers’ fault. Trego and the other salesman didn’t reply to phone calls and emails.

By late July, Sarah had had enough. She filed a complaint with her state insurance department. “New York State will start an investigation,” Strohmenger texted a Quick Health executive. “I will be the one that speaks for all of the people that have been scammed by this company.”

Normally, state regulators are the first line of defense against insurance companies that don’t pay claims or agencies that lie to customers. But the companies that back the fake-job plans aren’t insurance companies, and they contend that states have no jurisdiction over them. A few states have tried to ban the plans, with uneven success. Others, including Maine and Connecticut, merely advised the public to beware. When customers in Texas and Indiana complained about rip-offs, regulators there told them they were unable to help.

Plan sponsors contend the US Labor Department should oversee the plans, but that department doesn’t consider them real employers. That leaves the industry in a legal black hole where no one is responsible.

It took just one day for the New York Department of Financial Services to respond to the Strohmengers. “We apologize,” a representative wrote, “we are unable to resolve your complaint.”

“We apologize we are unable to resolve your complaint”

“We apologize we are unable to resolve your complaint”

“We apologize we are unable to resolve your complaint”

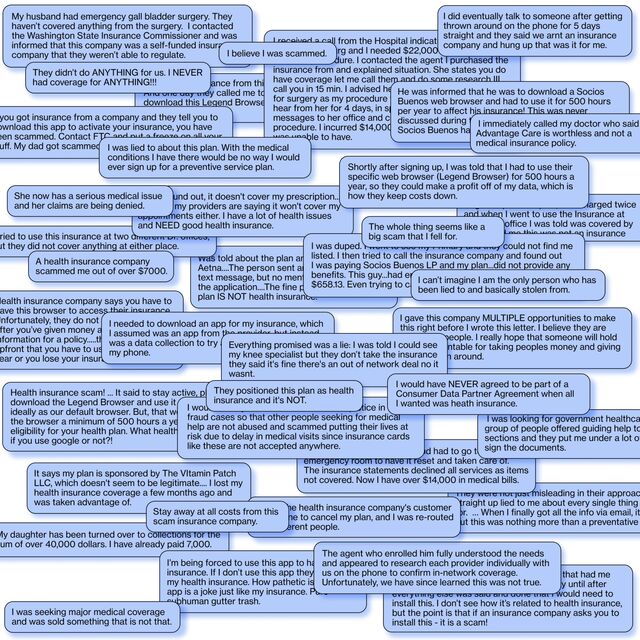

The Strohmengers’ experience parallels dozens of complaints filed across the country with the Better Business Bureau and state and federal regulators. Customers would buy plans from Quick Health thinking they provided comprehensive insurance. When they found out weeks or months later that the plans didn’t, they couldn’t get a refund.

“They positioned this plan as health insurance and it’s NOT,” a customer in Birmingham, Alabama, wrote to the Federal Trade Commission. From Dayton, Washington, another complained, “I gave this company MULTIPLE opportunities to make this right before I wrote this letter. I believe they are scamming people.”

Others were alarmed to receive papers showing they had become partners in a data-collecting operation, or were required to download an unfamiliar app. “I would have NEVER agreed to be part of a Consumer Data Partner Agreement,” wrote a customer in Cleveland. “All I wanted was health insurance.”

Still others, like the Strohmengers, didn’t recall ever hearing about an app, let alone an employment relationship.

Quick Health didn’t misrepresent the plans, doesn’t tolerate deceptive practices and has “refunded tens of thousands of dollars in good faith,“ Walsh says. He faults the health plans themselves for sometimes failing to pay valid claims, leading customers to point the finger at Quick Health. He says he switched to selling Obamacare plans last year. Bill Rush, a Quick Health lawyer, says the company’s regulatory scrapes are the result of misplaced blame and mistakes by previous counsel. As for the FBI search, Walsh said in a written statement that it “was part of a broad inquiry involving multiple entities” and that “we cooperated fully.”

“We try very hard — maybe because we are a rural, small agency, more a mom-and-pop type situation — to be very customer-centric,” says Walsh, who has since left the CEO job. “We want happy, repeat customers.”

But Quick Health salespeople were trained to exaggerate the plans’ benefits, says Brionna Myers, who worked in sales there for four years, until last spring. She showed Bloomberg a sales script that describes a fake-job plan as an “A-rate provider,” comparable to Blue Cross and Aetna but less expensive. “How I would pitch it, and what it actually was, is completely different,” she says.

Customers were constantly calling about expected refunds that never arrived, Myers says. The employee responsible for handling them was so notoriously stingy that a co-worker gave her a gag Christmas gift, Myers says — a license plate that said “NO REFUNDS.”

Consumers Complain

Hundreds of people have filed complaints with the US Federal Trade Commission, state regulators, the Better Business Bureau and Apple’s App Store about health plans tied to fake jobs and the insurance agencies that sold them. Here are a few.

Outreach isn’t the only company to occupy Box 371 in that strip mall in Atlanta. More than a dozen other entities have set up shop there, including Consumer Data Partners, American Partnership Group and Socios Buenos (“Good Partners” in Spanish). In all, these companies boast about 30,000 employees, which would make them one of the largest employers in the metro area. But Google them, and instead you’ll find complaints from all over the country about meager health plans and misleading sales pitches.

Not long after Bloomberg started calling people connected with the Box 371 operation last year, a public relations representative got in touch. Soon he was at Bloomberg’s office in New York with a wealthy Californian named Bill Bryan — the man behind the plans.

For a guy who wants to transform the US health-insurance system, Bryan, 66, has an unlikely résumé. For most of the 1980s and 1990s, he wrote for television sitcoms including Night Court and Coach. Later came a satirical novel about the reality-TV business.

Bryan says he parlayed his comedy earnings into savvy real estate deals and later ran a senior-living company and started an investment fund. By 2018, a regulatory filing shows, he’d amassed more than $20 million in investments.

During a three-hour interview, Bryan laid out his vision for providing affordable health care to the millions of Americans he sees as “left behind” by Obamacare, especially gig workers and other self-employed people. More than 20 million don’t have health insurance, and many who do complain about the price. Why buy an expensive plan, Bryan said, if you could never afford to pay the $9,000 deductible? The solution, he said, is to use the looser rules that apply to employer plans. “The goal is to level the playing field,” Bryan said. “We think everybody should be able to get their health insurance that way.”

Federal law forbids employers from turning a profit on benefits, so even though Bryan had the idea for the data companies, he can’t control or profit from them directly. Instead, he and his business partner, Arjan Zieger, who declined to comment, run a pair of Puerto Rican companies, Suffolk Administrative Services LLC and Providence Insurance Co. These firms handle almost every aspect of the data companies’ health plans, charging for plan design, administration and reinsurance.

In 2018, Bryan began distribution of the plans through a network of telemarketers, many in South Florida. The complaints to regulators and the Better Business Bureau started right away. (In a statement, Bryan said he has thousands of satisfied customers and that only a “very small fraction” have complained.)

“Long story short, it turns out that the coverage that i thought i had purchased is for all intents and purposes non existent,” wrote a Kentucky woman who’d been hit with medical bills after signing up for one of Bryan’s plans through a call center in Florida. “Nothing seems to be covered at all,” a Wisconsin man wrote to his state regulator. “I’ve never delt with anything this shady in my whole life.” The man said that after buying the plan from a Florida salesman, he called the number on the back of his ID card and was told he’d reached a Honda dealership. “Lady that answered the phone says she gets about 25 calls a day, even from doctors.”

In Indiana, a nurse practitioner named Brandy Dantzer says she bought a health plan from a salesman after he assured her it would cover her daughter’s pregnancy and delivery. It didn’t, sticking the family with $30,000 in bills. Bryan says plan documents made clear that maternity wasn’t covered.

The Indiana Department of Insurance told Dantzer it couldn’t help because she had an employee plan, she says — the first time she heard anything about being an employee. “For two years I was on the phone arguing,” she says. “It was all a fraud.”

Typical plans cost $200 to $400 a month, with some topping $900. In some cases, documents obtained through public-records requests to Wisconsin and Washington regulators show, the actual value of the plans’ medical coverage was as little as 26% of the cost, with the rest of the money going to sales commissions and other fees. By contrast, Obamacare plans are required by law to spend at least 80% on care.

Last year, in New York, Bryan was vague about who was selling the plans or how they got paid. He suggested some agents might be working for free. “There are things that we cannot control,” he said. “The truth is, and I will say this much, we don't really have visibility into all that.”

In a more recent interview, Bryan allowed that some agents might be earning big commissions. He said he would prefer to rely less on telemarketers, but a long-running court dispute with the Labor Department has kept traditional brokers away. He added that he’ll soon be offering plans with no commissions, sold by an in-house marketing team.

Bryan dismissed the notion that his plans ever denied valid claims, which are processed by licensed, independent administrators, and said he monitors agencies and terminates those with shady practices. Quick Health, he said, had been cut off years ago, after reports of misleading customers.

Told that Quick Health resumed selling his plans after that and was pitching people like the Strohmengers as recently as last year, Bryan said he was shocked. “That is absolutely news to me,” he said, his voice rising. “I just don't have anything more to say about any of these motherf---ers.”

He later added, in written statements, that his health plans shouldn’t be blamed for the actions of third-party marketers and that privacy laws prevented him from fully commenting on customers’ experiences. Quick Health, he wrote, “victimized many people, including the Strohmengers — and us.”

When Bryan first asked the Labor Department to sign off on his health plans, in 2018, congressional Republicans had just failed to repeal the Affordable Care Act, and the Trump administration was exploring other ways to permit cheaper, less comprehensive coverage. Bryan quickly found allies. Jeff Landry, then Louisiana’s attorney general and now its governor, rounded up six other Republican attorneys general to endorse Bryan’s plan. Landry didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Trump appointees at the Labor Department initially praised the idea, too. One urged Bryan’s group not to bother with formal approval, according to a court filing, but to “just do it.” So he did.

But then, in 2020, the department issued a six-page opinion concluding that web-surfing work wasn’t enough to turn health plan buyers into employees under the law. A Bryan-allied data company sued, persuading a federal judge in Fort Worth, Texas, to rule that the Labor Department got it wrong. An appeals court mostly affirmed that ruling but sent it back to the judge for further review.

In the latest twist, the Labor Department sued Bryan, Zieger and two of their companies in November, accusing them of improperly pocketing millions of dollars in an employee-benefits business separate from the fake-job plans. Bryan says the allegations are false and concocted to gain leverage in the other suit.

Meanwhile, the favorable court rulings attracted copycats. Using government filings and marketing materials, Bloomberg identified other so-called “employee” plans being pushed by South Florida telemarketers. Disclosures to the Labor Department suggest these competing plans now boast more participants than Bryan’s.

Fake Jobs, Real Growth

One, with more than 17,000 participants, enlists people in a multilevel marketing business to sell a nutritional supplement called the Vitamin Patch. “Our innovative, time-released topical patches are designed to deliver supplements directly through your skin and into your bloodstream,” the company’s website says. An investigation by Maryland regulators last year found that health-plan buyers “are not performing any work.”

Vitamin Patch LLC acknowledged in a statement that some enrollees claimed to be unaware of work requirements, adding that in recent months it took a “harder look” at its sales network, terminated bad agencies, strengthened vetting for new ones and “scaled back recruiting dramatically.”

Buyer Beware

Insurance regulators in Maine and Connecticut warned consumers last year to beware of "employee" health plans sold by telemarketers.

Bryan and his imitators are awaiting decisions that could bring their health plans to a broader market. The question of whether people like Joe Strohmenger are employees under federal law is back before the Fort Worth judge who previously said they were. He’s expected to rule in the coming months. But President Donald Trump, who promised to shake up Obamacare with vague “concepts of a plan” during his latest campaign, could order the Labor Department to stop contesting the case. The department referred questions to the Justice Department, which declined to comment.

A Bryan victory would at least make someone — the Labor Department — responsible for overseeing the plans. It would also encourage more salespeople to market them and keep state regulators at bay.

If the plans become popular enough, Obamacare’s defenders warn, they could blow up the private health insurance market. The idea behind the Affordable Care Act is to gather both sick and healthy people into the same insurance pool. If fake-job plans lured significant numbers of healthy people out of the pool, prices for those remaining could skyrocket, leaving the sickest uninsured. It’s what the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, in a court brief opposing the fake-job idea, calls a “classic insurance ‘death spiral.’” (In his statement, Bryan said he’s serving people who can’t afford or don’t want Obamacare and called the death-spiral scenario “absurd.”)

The ranks of uninsured Americans are likely to grow. Extra subsidies approved in 2021 helped millions sign up for Affordable Care Act plans for the first time. Those subsidies are scheduled to expire at the end of this year. Unless Congress acts, the number of uninsured may rise by almost 4 million, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Many might be tempted by telemarketers offering cheap alternatives.

Since taking the financial hit, the Strohmengers haven’t tried shopping for insurance again. Their second, more expensive Outreach plan has paid a few claims but rejected others for reasons they don’t understand. They say they never got any paperwork outlining their benefits.

Joe has stopped taking the blood-sugar medication and skipped almost a year’s worth of visits to the tumor specialist. “Hopefully, the universe is going to just keep us healthy and out of the hospital for a couple years,” Sarah says. “The universe could put this right somehow.”

(Corrects story published May 5 to reflect that lawsuit mentioned in 10th paragraph from the end was not brought by Bryan. Also adds explanatory note on time frame for graphic headlined “Fake Jobs, Real Growth.” )

Healthcare scams series nav

A Story Headline Another Story Headline Yet Another Story Headline and This One Is So Long There’s a Line Break