Contentious Copper Boom Sparks Existential Mining Crisis in Peru

The nation’s massive copper deposits are key to meeting growing global demand. A battle has emerged over who gets to mine and sell them.

An Indigenous community in the heart of the Peruvian Andes is doing what most of its peers in mineral-rich areas around the world aren’t: mining and profiting from their ancestral lands.

There, more than 13,000 feet above sea level, thousands of Quechua-speaking subsistence farmers have built what’s one of the largest informal copper mines in the world. The Apu Chunta quarry churns out about $300 million worth of the metal a year, funneling proceeds right back into the once impoverished community of Pamputa. It’s bound to earn even more soon: Copper — key to the global transition to clean energy — is already in short supply, as new deposits get harder to find and develop. Now, disruptions from threatened US tariffs have pushed prices to record highs.

There’s only one problem: What the Pamputa community is doing isn’t entirely legal.

In Peru, property ownership doesn’t grant rights to the minerals below the surface. So even though Pamputa’s residents have been herding alpaca and farming their land for centuries, the $10 billion-plus Las Bambas mine, now owned by China’s state-controlled MMG Ltd., purchased the rights to the copper ore under them in 2004 from the Peruvian state.

Las Bambas Is on a Collision Course With Indigenous Miners

The giant copper mine is locked in a land dispute with informal diggers

That has put the Pamputa community on a collision course with MMG and the Peruvian government, zealous to protect the single largest investment ever made in the mining nation. Las Bambas has already built two pits in the mountains neighboring Pamputa and earmarked the Indigenous group’s land for a third, set to open in the mid-2030s. It has also filed more than 100 illegal mining complaints against the Indigenous miners in Pamputa. The complaints are pending and the miners are defending themselves through lawyers.

“We are aware of the presence of illegal mining activities within our concessions,” Las Bambas said in a statement. “The significant increase in illegal mining activity across Peru is a challenging issue that has the potential to affect future large-scale investment.”

For now, Apu Chunta is partly backed by a government-run registry of informal mining operations. But Las Bambas argues that the miners should be struck from the registry, accusing them of stealing the company’s copper. The registry expires in June and could have ended earlier if not for mass protests that blocked highways and triggered the dismissal of the then mining minister, who wanted to crack down on informal operations.

How the dispute between the Pamputa community and MMG plays out could redefine the balance of power in the mining industry, from the most remote stretches of the Peruvian Andes — home to much of the remaining large, accessible copper deposits — to what ends up in consumers’ pockets and homes. The ore that’s pulled from Indigenous mines winds its way through a long supply chain, from local processing plants and global trading firms to Chinese smelters and all the intermediaries in between, and finally into wire that’s in everything from mobile phones to electric vehicles.

If the Pamputa are able to assert their ancestral claims over MMG’s contractual rights, it would further embolden artisanal operators — and discourage big miners from spending the billions of dollars required to find and develop new deposits. And because informal miners simply don’t have the resources to efficiently mine giant deposits, that would limit future shipments and further squeeze global supplies of the wiring metal.

Typically, a project like Las Bambas would try to win over locals with some financial incentives and pledges to minimize environmental damage, but Pamputa’s residents don’t see the point. They view mineral rights holders like MMG as a new form of landholding aristocrats, the kind that controlled Peru’s agricultural lands up until the mid-20th century while preventing Indigenous groups living there from profiting from that land.

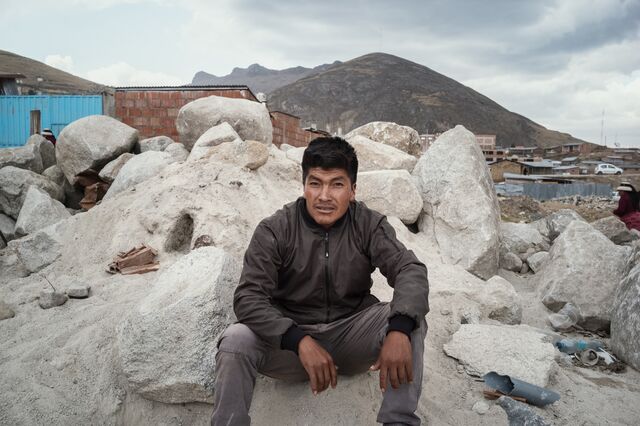

“We are no longer in the time of Robin Hood — taking from the rich to give to the poor,” said Nelson Pinares, who presided over the mine through last year and now oversees a project to build a processing plant there. “What we want is to give the poor the same opportunities so they can also become rich.”

At least for now, Apu Chunta is thriving thanks to community support, an ambivalent government and perhaps most of all: willing buyers amid the surge in global demand for copper.

Pamputa’s once-sleepy village sustained by small crops and livestock is being completely revamped. Multistory brick buildings are rising. New roads, school buildings and a town square are under construction. Residents come and go in new $20,000-plus Toyota Hilux pickup trucks, and some have even bought expensive race horses. Pinares owns some animals in Lima’s aristocratic racecourse.

There’s good money to be made from the metal regardless of who mined it — but maybe even more so if it comes from an informal mine.

Indigenous producers have less bargaining power with the processing plants and intermediaries that purchase their ore, which can be blended with other material to boost buyers’ profits, people familiar with the global copper trade said in private conversations.

Plus, given that much of the world’s copper is contracted out in advance, informal output can also give trading firms the option to tap the open market when there are shortages.

So, despite lacking the right permits, copper from mines like Apu Chunta is making its way to some of the biggest traders in the world.

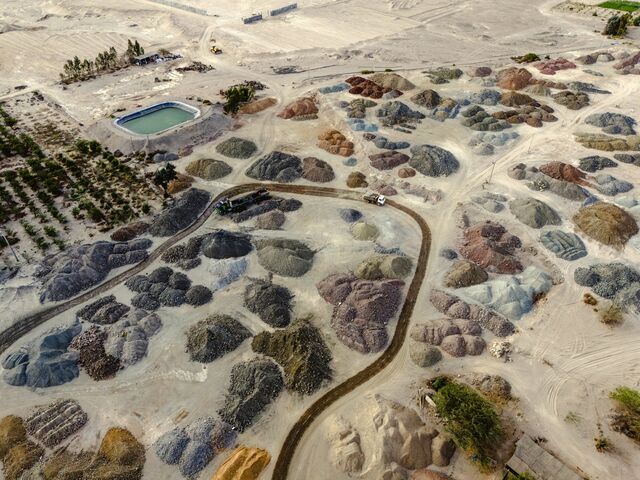

This is how it happens: After rock containing copper is unearthed, some miners pay “invoicers” to act as a legal front for their minerals. Then, drivers transport the goods to the booming coastal city of Nazca, where more than two dozen plants transform the raw minerals into concentrate. While they may ask for legal certification, they don’t dig much deeper than the paperwork that comes with the rock.

“The processing plant can receive the mineral, transform it, and it can come out in a — quote unquote — legal manner,” said Paola Bustamente, a former development minister who recently produced an industry-funded study on illegal mining.

The plants sell the semi-processed copper to traders, who ship it to Chinese smelters that transform it into metal for wiring used in a range of electrical goods. According to Pinares and close to a dozen sources, traders include Trafigura Group, Glencore Plc and IXM SA.

Most people interviewed for this story only spoke anonymously because of fear of running into legal trouble, such as investigations should authorities suspect they were working with illegally sourced minerals. But export records show that Trafigura and IXM have shipped $1.8 billion worth of metals, mainly copper, since 2019 originating from the Ica region, which includes Nazca. In 2023, the most recent data available, IXM’s exports from the area jumped 78% to $344 million.

Trafigura, Glencore and IXM all say they are compliant with Peruvian rules, buying only from registered entities.

“We are also committed to responsible business practices and we encourage our counterparties to also act responsibly,” a Trafigura spokesperson said in a written response to questions.

Besides its standard screening procedures for suppliers, Glencore carries out additional checks in Peru, “including in respect of their registrations, permits, and information regarding environmental management instruments,” the Swiss commodity giant wrote.

How Peru’s Informal Copper Reaches Traders and China

Informally mined copper is legalized through processing plants

While IXM buys from processors in Nazca, it only does so from plants registered in Peru’s informal mining registry, known as Reinfo, the firm said in a written response. Apu Chunta is a part of the Reinfo registry. IXM only deals with “reliable long-term counterparts at market-based terms,” which it screens and monitors. The firm is also piloting a program in Peru to support smaller miners.

It’s frustrating for big miners like MMG, who say third parties are making money off of copper earmarked for them. Peru’s powerful mining society, SNMPE, recently summoned commodity trading firms to answer questions on the issue after being contacted by Bloomberg for this story.

“A production chain has been created, but this production is intrinsically born out of minerals that belong to third parties,” said Victor Gobitz, who until January was SNMPE’s president.

“Is it ethical? I think that does raise all of our eyebrows,” added Gobitz, who is also the former chief executive of Antamina, one of the country’s largest copper mines, which is one-third owned by Glencore. Trafigura and Glencore are both members of the SNMPE.

Gobitz has since taken the helm of a new copper startup, Quilla Resources Inc. to restart the Chapi mine in Peru.

The government of Peru — the world’s No. 3 copper producer — also sees informal miners as a threat to one of its largest sources of tax revenue: the mining royalties paid by corporations, which small-scale miners do not pay.

Peruvian Prime Minister Gustavo Adrianzen said in an interview that “illegal miners” do not face the same social stigma as drug traffickers in Peruvian society — but they should.

“In Peru, the illegal miner is perceived as an entrepreneur, as a worker,” he said. “But we want to promote, strengthen and protect formal mining, like Las Bambas.”

There’s a legal gray area that allows small-time miners to run their mines in the first place.

The government oversees a mining registry called Reinfo, which allows informal groups to operate as long as they have both the permission of the owners of the land and the mineral rights.

The Apu Chunta workers are registered in Reinfo and they own the land they’re extracting from, but don’t have the blessing of Las Bambas, which owns the mineral rights. And they never will, the mining giant said in a claim it filed against Pinares and other locals in May.

“We are seeing several Indigenous farming communities that are becoming mining communities,” said Maximo Gallo, who was recently appointed as Peru’s top mining formalization official.

Experts estimate about 200,000 Peruvians work in the industry, with half of them now mining copper. Over 90% of them are working in concessions that don’t belong to them, according to government statistics.

Peru’s mining association SNMPE and other groups have for years failed to convince congress and the government to end the registry. But the informal miners have also become a political force: When the mining minister tried to end the Reinfo registry in December, thousands of small-scale miners blocked key highways in protest. Congress fired the minister and lawmakers instead opted to extend Reinfo through at least June. The new mining minister hasn’t ruled out extending it through December.

Still, Reinfo has failed at its mandate of encouraging big mining to give permission to informal miners to work on their unused land. In the seven years since Reinfo started, only 2% of the 80,000 mines have been formalized.

MMG isn’t the only big mining corporation that has been affected. Informal mining operations have disrupted development at projects owned by Southern Copper Corp. and First Quantum Minerals Ltd.

Elsewhere, it has resulted in violence, as informal miners have been accused of killing over a dozen workers at Peru’s second largest gold mine, Poderosa, in a dispute over mineral rights. Large miners now fear that all early-stage exploration projects are attracting informal operations long before they can get permits to build a mine there.

Informal miners stand accused of twice burning down the camp set up by Southern Copper at its Los Chancas project, most recently this month. The mine will be built no earlier than 2030 for an estimated $2.6 billion, but it has already attracted the local Indigenous community to try its hand at mining it without permits.

The problem extends beyond Peru’s borders. The Democratic Republic of Congo has in the past deployed the military to evict thousands of illegal copper and cobalt miners. In the Brazilian Amazon, high prices of copper have attracted illegal operators who normally focus on gold. Informal mining is also widespread in Bolivia and Ecuador as well as in other African and Asian nations.

Big mines also argue that informal operators don’t have the exploration and planning capacity to extract ore efficiently and safely, with a lack of permitting and lax labor practices adding to the environmental and worker risks.

Mining is already one of the most dangerous jobs in the world, and informal operations have little state supervision over safety or environmental protection. Apu Chunta has reported at least two deaths, while workers say they have witnessed child labor and alcohol consumption. Pinares would not allow Bloomberg reporters to visit the Apu Chunta site, but said both practices were banned with any perpetrators punished.

Indigenous, informal miners in Peru have won folk-hero status in their communities, making political attempts to remove them that much tougher.

Interviews with dozens of people around Pamputa show the Apu Chunta mine has earned support for employing unskilled miners who are shunned by Las Bambas. That’s put cash directly into the hands of people who do not see the supposed trickle-down effect that the big mine’s taxes are supposed to have in the area.

Even though Las Bambas represents 75% of the region’s gross domestic product, the local governor recently declared that he supported extending Reinfo.

“Having Las Bambas so close hasn’t benefited this population at all,” said Zenovio Flores, the deputy mayor of the neighboring town of Nahuinlla. But that’s not the impression when it comes to Apu Chunta. “Artisanal mining has brought considerable opportunities and benefits with regards to development of the population.”

Las Bambas disputed this characterization, which is widespread among local residents. The company said it had spent $800 million on local suppliers between 2016 and 2024, and that it was helping build community-owned companies so that local Indigenous populations could become part of their supply chain — and cash in. It also said it wanted to make sure its third pit at Pamputa was “operated sustainably and in a way that benefits host communities.”

Pinares says the workforce of Apu Chunta has multiplied more than 10-fold in a decade, now employing 5,000 miners and having created another 5,000 indirect jobs.

The town even owns a professional soccer team, Union Minas— which roughly translates to Mining Union — with a logo featuring a typical yellow mining hard hat.

Francisco Perez has worked in informal mining for more than a decade. While there are hazards — pollution and dust inhalation — he’s grateful to Apu Chunta because he’s been able to build a house out of bricks to replace his previous adobe hut.

The artisanal copper boom has also trickled down to nearby towns where new businesses offer equipment, supplies, meals and lodging. Shops sell helmets, carts, compressor accessories and even mining figurines. Mining trucks casually park in the town. Some residents store machinery next to their homes.

It’s a stark contrast to when Las Bambas first entered the area in the early 2000s. It paid more than $1 billion to resettle one community in order to build its first pit, and spent tens of millions to buy the land of another village for its second.

Both experiences were traumatic for the Indigenous communities, even if they received vast sums in exchange. The first community, Fuerabamba, tried to reclaim its land in 2022, saying selling had been a mistake and that the money it received had dried up. Las Bambas eventually evicted them by force with the help of police.

Las Bambas already holds mineral rights in the province where Apu Chunta is located, totaling almost 35,000 hectares, about the same size as Philadelphia.

In all, 94% of the area’s mineral rights have already been claimed by third parties, according to nonprofit Cooperaccion. Those areas are all owned by Indigenous groups of fewer than 1,000 people who are not supposed to mine their land — yet they increasingly do.

That has all given the Pamputa people perspective on their situation. Pinares’s sister, Sandra, who is also a mining leader at Apu Chunta, is opposed to simply selling like the two neighboring villages.

“I think it is better to keep the cow and its milk, even if it flows only little by little,” she said, “than sell the cow and end up with nothing.”

Assists: Jack Farchy, Archie Hunter and Cedric Sam

Editors Responsible: Simon Casey and Crayton Harrison

Editor: Danielle Balbi and Doug Alexander

Photo Editor: Marie Monteleone