This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Not long ago, Rob Lowe was in Atlanta, shooting a small movie he won’t tell me the name of, when he ran into a problem. “Our camera department was having a hard time getting certain shots because the dolly grip wasn’t hitting his marks,” he says. A Marvel project was filming nearby, along with three or four other large-budget movies, and by the time Lowe and his team arrived, the city’s most experienced crew members were booked elsewhere. “It turned out that our dolly grip had never been on a set before,” Lowe says. “He’d applied for the job because he’d worked a dolly at Costco.”

For 25 years, Lowe has starred on one hit network-TV show after another, including The West Wing, Brothers & Sisters, Parks and Recreation, Code Black, and 9-1-1: Lone Star, which wrapped production on its final season last year. Every single one was shot in the same place TV shows and movies have always been shot and where there’s rarely a shortage of veteran dolly grips: Los Angeles. If it were up to Lowe, he would do all his work in the city where he can sleep in his own bed and be home in time for dinner. “I’ve been fortunate in that I’ve had the ability to mandate it. 9-1-1: Lone Star was originally going to shoot in Austin, and I told them that wouldn’t work for me,” he says. But lately, filming locally has been more difficult and often flat-out impossible. “The state of the business is so bleak now,” Lowe tells me, “that even I am willing to consider shooting outside of L.A. because the opportunities here have just gone away.”

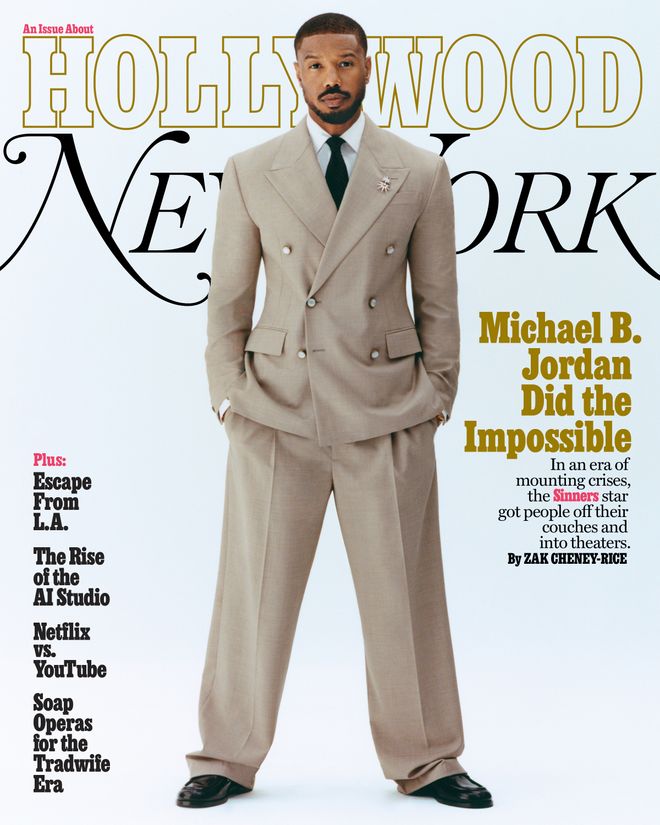

The Hollywood Issue

The past decade has been tough on Hollywood — both the industry and the place. L.A. has endured a parade of black-swan catastrophes that have repeatedly upended its signature business, including fires, strikes, COVID, the decline of movie theaters and linear TV, and streaming’s boom and bust. Taken together, these disasters have triggered something like an identity crisis. If you call up a couple dozen executives, agents, directors, producers, writers, actors, and below-the-line artists and ask about the scene on the ground right now, they’ll describe a city detached from its old rhythms and sense of purpose. Today’s L.A., a few say, feels more like a Rust Belt crater than the glamorous capital of the world’s entertainment. “It’s so grim, like a sad company town where the mill is closing,” says one executive. “It’s morose, and everybody’s scared,” says the actor and director Mark Duplass. “It’s a bummer to live here now,” says a writer.

Pieces of the business still hum along in the city, albeit more quietly than they used to. Executives and agents are back in the office, at least the ones who weren’t laid off. Pitching and deal-making continue, though much of that now happens over Zoom. But production — the physical process of turning script pages into movies and TV shows — has largely left town. What began years ago as a trickle has suddenly become an exodus. Today, only about a fifth of American movies and shows are filmed in L.A. According to FilmLA, a nonprofit that tracks permits and has monitored production levels for three decades, 2024 was the worst year on record for local filming, aside from 2020. Even 2023, when the industry was frozen by strikes for nearly six months, saw more activity. And 2025 is off to an even worse start, down 23 percent so far compared with last year. None of 2024’s ten highest-grossing live-action movies was shot in L.A. Nor was a single one of this year’s Best Picture nominees. “These back lots are ghost towns right now,” says Power creator Courtney A. Kemp.

Even movies set in L.A. are increasingly filmed elsewhere. Last year, that included The Substance, shot in Paris, Antibes, and around Cannes and Nice; and Netflix’s Carry-On, which was made in New Orleans. These are scenic places in their own right, of course, but none is quite up to the role. “Making other cities look like L.A. is just not really possible,” says production supervisor and location manager Caleb Duffy. “We’re too identifiable. We’re an international city with too many iconic places to re-create anywhere else. The streets are different; the trees and foliage are different.” Nevertheless, this year, Russell Crowe is reportedly filming the L.A.-set thriller Bear Country in Queensland, Australia.

As the labor of making movies and shows splinters across far-flung cities and countries, Hollywood has become dislodged from its physical home. Some of these new hubs may suit the needs of individual projects, but none of them offers what L.A. did for most of the past century: a stable gravitational center where crews can make a living and the craft can be passed down. This isn’t just a logistical reorganization; it’s an existential shift, and there may be no going back. “The nucleus that Hollywood grew out of is dying,” says Jonathan Nolan, the writer-director whose work includes Person of Interest, Westworld, and Fallout. “I don’t think Hollywood the industry has much to do with Hollywood the place anymore,” says Lowe.

One reason L.A. even became a city at all is because it was a great place to make movies. (It helped that it was far enough from New Jersey to escape the enforcement of Thomas Edison’s patents on motion-picture cameras and projectors.) The weather allowed for year-round outdoor shooting, attracting the industry’s best filmmakers, actors, and crews. This created a self-reinforcing bubble in which the top talent was all concentrated in the same place; this, in turn, supported an informal apprenticeship system under which younger crew members learned on the job, providing a steady influx of skilled labor. For a long time, there was usually no good reason to shoot anywhere else.

Then, in the 1990s, British Columbia hatched a plan to bring some of that action north. The Canadian provincial government introduced one of the world’s first film tax credits — a financial incentive meant to lure foreign productions — offering a modest rebate on money spent employing local crews. It worked, and many U.S. states took notice. In the early aughts, Louisiana and New Mexico rolled out flashy credits of their own, transforming New Orleans and Albuquerque into viable production hubs.

A short while later, streaming boomed, and the demand for scripted entertainment exploded. With more production in play, regions around the world began ramping up their incentives, and many built soundstages and crew bases that could compete with those in L.A. What followed was a global bakeoff for Hollywood’s business. Canada, the U.K., and Australia enhanced their already aggressive tax credits, often made even more appealing by favorable exchange rates. Many U.S. states, including Georgia and New York, followed. Before long, most of the country, and dozens of countries beyond, were offering some version of a production subsidy.

These incentives can be shockingly generous. Today, producers can shoot in certain locations and receive back 30 to 40 percent of a project’s budget with local taxpayers footing the bill. Unlike traditional tax breaks, which merely reduce what a company owes, these credits often amount to direct cash payments, issued regardless of whether the production generates significant tax revenue in return. New York State, for example, offers a 30 percent base tax credit with a 10 percent bonus for projects made upstate. Last year, New York tax dollars helped subsidize TV shows including HBO’s The Gilded Age (which received $52 million from state coffers), Prime Video’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel ($46 million), and Apple TV+’s Severance ($39 million). An Albany-funded audit of New York’s film tax credit, published last year, determined that the incentive is probably a net loss for the state, returning as little as 15 cents in direct tax revenue for every dollar spent. Regardless, in May, New York added an additional $100 million for independent films, bringing the state’s total film subsidies to $800 million.

Meanwhile, California mostly sat on its hands, assuming its long-standing monopoly on talent and infrastructure would be enough to keep Hollywood anchored. Subsidizing an industry already based there was a tougher political sell, but the state introduced its own incentive program in 2009 and has sweetened it since. Unfortunately, while the credit may sound generous, in practice it’s miserly to the point of uselessness. California refunds just 20 percent of the first $100 million a project spends and excludes the salaries of directors and actors, which are often the biggest line items. The program also has an annual cap of $330 million, meaning many productions are turned away and end up filming elsewhere — including Georgia, where the credit is uncapped and virtually guaranteed to any project that desires to shoot there. On top of that, California enforces some of the world’s strongest union protections, which translate to higher labor costs that can push producers toward locations with weaker ones.

When the streaming bubble burst in 2022 and studios slashed their content budgets, tax credits became even more essential because the companies still spending were determined to spend less. “It was always true, even before Netflix, Amazon, and Apple jumped into production, that studios wanted to make things as cost-efficiently as possible,” says The Good Place creator Mike Schur. “But I think cost-efficiency is now the primary focus of a lot of TV and film production in a way that it didn’t used to be. And oftentimes that means shooting in Atlanta or Vancouver or Toronto or Croatia or Moldova or whatever.”

Now, whenever a studio green-lights a project, it runs the numbers and finds that, usually, the cost of filming in Los Angeles is too steep. “If you’re a publicly traded company and you want to turn a profit, it’s your fiduciary responsibility to go shoot somewhere else,” says Lowe. “With these economics, you’d get fired otherwise.”

On large productions, the difference can be staggering. For blockbuster movies, whose budgets now routinely exceed $300 million, California’s puny tax credits can easily make filming in L.A. tens of millions more expensive than in other locations. “I know producers who won’t even make a paper budget for L.A, meaning they won’t even try to figure out how much it would cost here because they know it’s just too much,” says Nolan. For smaller projects with tighter margins, these differences can be just as critical. The 2024 horror movie Night Swim was shot in L.A. on a reported budget of $15 million and grossed $32.5 million in North American theaters. “Shooting in L.A. cost us an extra $4.5 million,” says Jason Blum, the founder of Blumhouse Productions. “In retrospect, it was probably the wrong decision.”

It’s slightly more feasible to make TV shows than movies in L.A. since their costs can be amortized over episodes and seasons, but increasingly only for creators with enough clout to demand it and only if sacrifices are made. Nolan is now filming the second season of Amazon’s Fallout a little north of L.A. in Santa Clarita, helped by a bonus 5 percent tax credit that benefits shows relocating to California from elsewhere. (The first season was made on soundstages in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.) But it’s still more expensive than New York, so Nolan agreed to cut 18 days from this season’s production schedule. “That money comes off the screen,” he says. Likewise, Max’s recent medical drama The Pitt was able to shoot locally in part thanks to its nontraditional salary scale, which brings the show’s budget down on par with what a tax incentive might have done. (The show costs $4 million to $5 million per episode). “We paid our cast using a tiered system that eradicated the ability to negotiate or apply a previous quote to this contract. It was a take-it-or-leave-it proposal,” says Noah Wyle, The Pitt’s star and executive producer. “You’d be surprised how many people cut their usual rates to stay close to home.” Schur tells me that the first season of his Netflix comedy A Man on the Inside, starring Ted Danson as an amateur PI set loose in a retirement home, could shoot in L.A. because 85 percent of it was made on the same no-frills soundstage, which was set up so episodes could be shot quickly. Also, “a lot of our actors are in their 70s and 80s and even 90s,” he says, so it’s not like he can take them to Croatia.

Politicians love film tax credits because they’re a fast and sexy way to create jobs. Opening a new manufacturing plant, if such a thing were even possible, would take years of planning and huge investment, but if a state offers the right incentives, film crews can show up practically overnight. The problem is that those crews can pack up and leave just as quickly; production is fickle, mobile, and loyal only to the biggest offer. Louisiana, which briefly held the nickname “Hollywood South” after its credits lured True Detective and Jurassic World in the 2010s, lost much of its business when Georgia and other states offered richer deals. More recently, most of the Marvel Cinematic Universe relocated from Georgia to London to take advantage of the U.K.’s lucrative credits. Several industry members tell me Saudi Arabia could be the next magnet.

This means the people who make our entertainment, many of whom still live in L.A., now rarely know which city or even which continent their next job will take them to. “I just had an amazing opportunity to make another TV series, but at the last moment, they decided they wanted to shoot in New York and I said ‘no,’” says Lowe. “So I’m trying to figure out what I’ll do instead, and one of the candidates is a miniseries but it would shoot in Australia. I told them that was a nonstarter because with the time difference, you might as well be on the International Space Station.” Lowe currently hosts the Fox game show The Floor, which films in Dublin — even though that requires flying 100 American contestants there for each season and even though Fox has plenty of perfectly good soundstages in L.A. He tolerates it because he can shoot a season of The Floor in a week.

This unpredictability is especially destabilizing for the makers of scripted TV series, which can require open-ended commitments to live in faraway locations for months at a time, year after year, for as long as a show is on the air. And it may hit below-the-line film and TV workers the hardest. These are the crew members who don’t command marquee salaries but once managed to build lives in L.A. simply because that’s where the work was. Now, with no centralized hub and fewer jobs overall, their lives have become nearly impossible to plan. “This is definitely the biggest dip that I’ve seen since 2008, and it seems to have stretched out a little longer than that period,” says Duffy, the production supervisor, who is currently working in L.A. on the fourth season of The Lincoln Lawyer but was unemployed for five months after the show’s third season wrapped last year. “So now I’m looking for work in other states and other countries, too. I’m open to anything because there’s such a lack here.”

One crew member, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of jeopardizing future employment, says he moved from his hometown of Atlanta to L.A. in 2015 hoping to break into postproduction but couldn’t get a foot in the door. “I was working in a noodle shop to survive, and I was like, This sucks,” he says. He moved back to Atlanta, which had become a production hot spot, and almost immediately found himself in demand as a second camera assistant. Between 2017 and 2022, he says, he worked steadily on major TV shows and blockbuster films. “I could go out to a bar in Atlanta and there would be three different crews from three different TV shows there, and once, without even trying, I came home with a job.” Then came the 2023 strikes and the streaming contraction. Stranger Things, which had filmed five seasons in Atlanta, wrapped its final one in 2024. Marvel left the state. Local crew members had to compete for dwindling jobs with Californians and New Yorkers who had moved to Atlanta during the boom. “Things still haven’t picked up,” he says. “I have friends ask me why I can’t just get another job. I tell them, ‘Imagine if you were an accountant and every accounting job suddenly moved out of the country.’ ”

The relocation of production isn’t just a threat to Hollywood’s economy; it’s unraveling the apprenticeship system that helped build it. “These sets are teaching hospitals. If the doctors don’t learn how to do the job, pretty soon there’s no doctors,” says Schur. “I just think that the industry has its priorities all wrong and that it’s dramatically undervaluing the benefits of having a stable workforce in a stable place where the vast majority of the business is located. You can’t just microwave a talented crew of people in every city in the world every time a new city gives you a tax break.”

This matters to viewers, too, since it changes what shows up on their screens. “Look at This Is Us,” says a top-level agent. “It was made in L.A., on the Paramount lot, and the creator’s office was eight feet away from the stage. It ran for six years, and the stars weren’t dying to end it, probably because they were living at home.” The agent compares it to another show that premiered around the same time but was canceled after three seasons. That show filmed in Toronto, where, unlike L.A., the soundstages are located all over the city instead of concentrated in the same neighborhoods. “The studio went for the biggest tax credit it could find, but the problem was that Toronto is more spread out. The distance between the closest stage and the eighth-closest stage is like the distance between shooting on the Fox lot and in Santa Clarita,” the agent says. “The star’s hotel was 55 minutes away from the set, and everything ran late. So they would start shooting at six every night and wouldn’t finish until six the next morning. Also, the showrunner wasn’t on set because the writers’ room was in L.A. So This Is Us was golden. The other show was a disaster.”

Now that the crisis is too big to ignore, some are waking up. Last year, California governor Gavin Newsom proposed lifting the annual cap on the state’s tax credit from $330 million to $750 million, which many say would help, especially since L.A.’s production infrastructure still counts for something. “California wouldn’t need to have the most aggressive incentive to bring business back,” says Lowe. “It would just have to be better than it is now.”

This is a bidding war, though, and if California expands its credit, there’s a chance other places will expand theirs, too, which could leave L.A. at the same disadvantage. “We’re in this tricky situation now where we’re waiting with fingers crossed that some of these other jurisdictions decide that tax credits aren’t worth the money,” says Paul Audley, president of FilmLA. “In retrospect, when Vancouver started this 30 years ago, California could have said, ‘No, wait, this is ours,’ and slammed them down with a competitive credit of its own. But nobody could have imagined then that so much of the industry would leave.”

Perhaps resigned to production’s permanent decentralization, a growing number of actors and entrepreneurs are hoping to redirect some of the opportunity to their own backyards. Mark Wahlberg is building a new studio complex in Nevada. Kevin Costner is doing the same in Utah. Zachary Levi is raising money for his own $100 million studio near Austin. Meanwhile, Matthew McConaughey, Woody Harrelson, and Dennis Quaid recently starred in an ad for the “True to Texas” campaign asking lawmakers to expand the state’s film incentives.

Last month, into these waters waded President Trump. “The Movie Industry in America is DYING a very fast death,” he posted on Truth Social on May 4. “Other Countries are offering all sorts of incentives to draw our filmmakers and studios away from the United States. Hollywood, and many other areas within the U.S.A., are being devastated.” Declaring a “National Security Threat,” the president announced a tariff of 100 percent on all movies “produced in Foreign Lands.” The idea was planted by Jon Voight, who had recently visited Mar-a-Lago. The Midnight Cowboy star — one of Trump’s three “special ambassadors to Hollywood,” along with Mel Gibson and Sylvester Stallone — pitched the president on a tariff that would cancel out any internationally provided tax incentive for movies that “could have been produced in the U.S.” but were not. Voight’s proposal, which later leaked online, also recommends a federal film tax credit of 10 percent that can be added to any state incentive, plus a 5 to 10 percent bonus credit for shooting in “economically depressed” areas, which would include California.

How do you enforce a tariff on a movie? “I have no idea,” admits Scott Karol, a film producer who helped write Voight’s proposal and attended the Mar-a-Lago meeting. “Because a film is digital and not really a physical good that comes into the country.” But Karol says the more important part of the plan is the federal credit, which he thinks will be sufficient to entice more productions back to the U.S. and maybe even L.A. “If you offer these carrots, there will be no need for the stick.”

That credit, though, could face an uphill climb through a Republican-controlled Congress that seems unlikely to vote for anything that would so lavishly benefit pinko Hollywood. And even if it did pass, there’s no guarantee it would stop the bleeding in L.A. It might just as easily steer projects to other states.

A week after Trump’s announcement, representatives from the Hollywood unions and major studios signed a letter endorsing the federal incentive but omitting any mention of a tariff. Those guilds represent talent across all 50 states, meaning their priority is keeping jobs within the U.S. more broadly. (The crew union, IATSE, also represents workers in Canada.) And the studios include streaming companies whose ultimate loyalty is to the bottom line.

“I don’t know that the major studios care if production stays in Los Angeles,” says an agent. “I don’t think they see it as existential. Apple makes all of its phones in China. Amazon Web Services is all over the place, wherever the warehouses are cheap. Why the fuck would they care where these movies are made?”

On January 7, after smoldering for so long in so many anxieties, L.A. finally went ahead and burst into flames. Propelled by hurricane-force winds, the fires devoured movie stars’ houses in Malibu and Pacific Palisades and then torched the homes of the industry’s middle class in Altadena and Pasadena. David Lynch died shortly after evacuating his house, robbing L.A. of its unofficial mascot — the rare filmmaker who could distill all the city’s beauty and rot into a single hallucination. In a town that has produced more than its share of unsubtle symbolism, the fires overdelivered.

Lesli Linka Glatter, the TV director and president of the Directors Guild of America, had been in a meeting that day when she got a call from a friend. The Palisades neighborhood where she’d lived for more than 20 years was being evacuated. Her home burned down that night. And yet, she says, she’s lucky: “I hate to say this, but there are a few houses still standing in my neighborhood, and in some ways that would be worse. You can’t move in, and who would even want to? Everything around you is destroyed.”

She has decided not to rebuild, Glatter says, and it’s hard to blame her. (She’s currently renting a place in another L.A. neighborhood.) For those willing to, the process will take years. A typical insurance payout may cover only a portion of the rebuilding costs at today’s prices — but those prices are likely to skyrocket when the entire neighborhood competes for the same builders and materials. (“You’re going to have 5,000 people who all want the best architect, and it’s going to be a fucking nightmare,” says a top-level agent.) Securing new insurance coverage on a rebuilt home may also be difficult, since California’s biggest insurers stopped issuing new policies in the state in 2023. Environmental groups say the ground soil could now be toxic and that any lithiumion batteries left behind may have been baked into land mines.

Glatter will be fine. So will the Palisades residents whose houses survived, including Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg, damn their miserable luck. But the aftereffects of this disaster will likely be felt beyond just the burn zones. As the map of livable L.A. shrinks, so does the footprint of its production infrastructure. Entire neighborhoods that were once home to directors, cinematographers, editors, designers, and grips are now uninhabitable or uninsurable. The exodus of industry professionals, which was already underway owing to the high cost of living, will probably accelerate as many wonder whether it’s worth it to live in a city that’s harder to shoot in and now more frequently on fire.

Lowe is hopeful the rallying effect of the past few months could push California lawmakers to make the state’s tax credit more competitive. “It’s ironic that it literally took the town burning down to make it happen,” he says. “But since the fires, I feel an energy around revitalizing our industry that I haven’t felt in years.”

Then again, the city so many are trying to save may already be a memory. “I’ve lived in L.A. my whole life, and I’ve seen the city go through a lot, but this was different,” says Wyle. “Some of the homes that burned down were 100 years old. These neighborhoods will change, and we’ll lose a lot of character in the process, and L.A. will become less special photographically. One of the great advantages to shooting here is that you’re still able to re-create some of the city’s past and tap into its lore. But the more it begins to look like any other place, the less you’re able to do that.”