Businessweek | The Man Meltdown

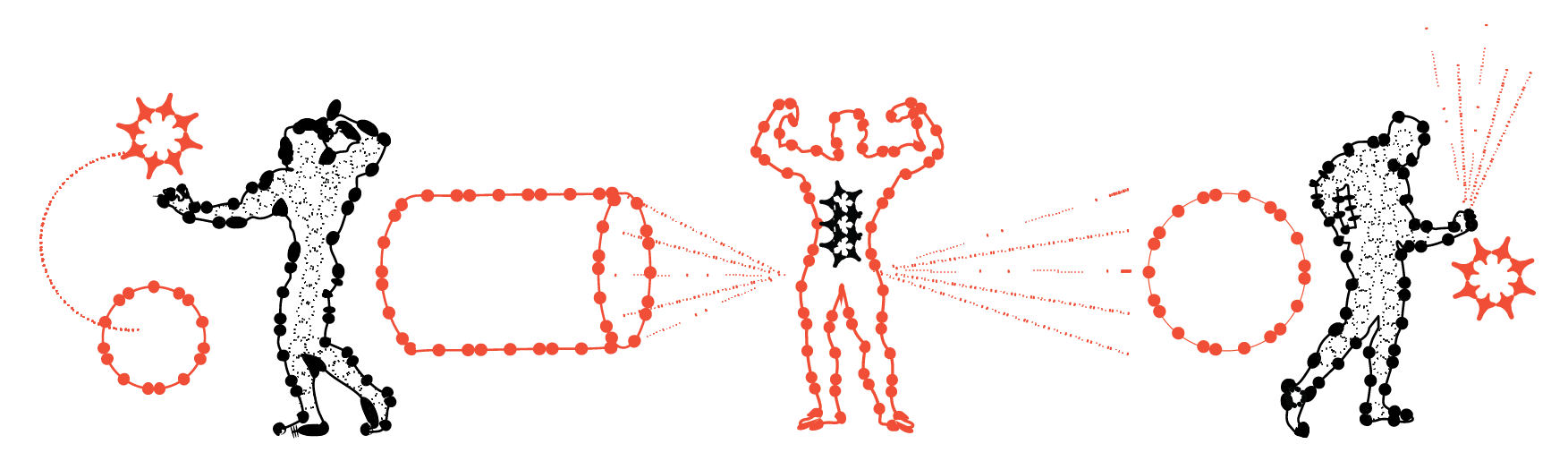

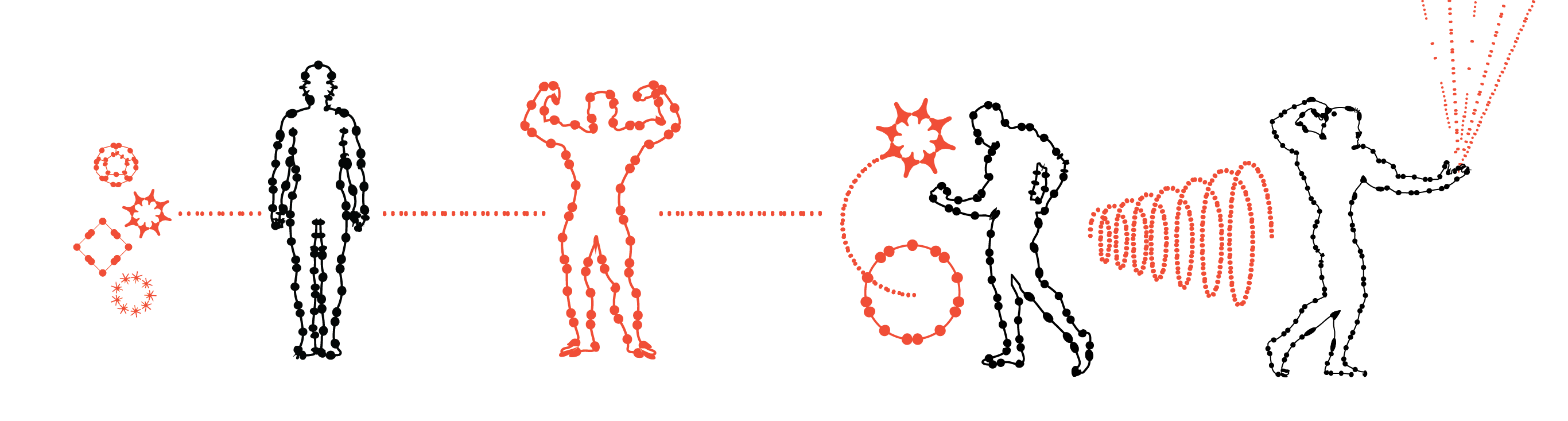

THE EVOLUTION OF THE ALPHA MALE AESTHETIC

IF YOU’VE NOTICED A CERTAIN LOOK COMMON TO THE MANOSPHERE, YOU’RE NOT MISTAKEN. A VISUAL IDENTITY HAS TAKEN HOLD, WITH ROOTS THAT TRACE BACK DECADES.

In the mid-19th century, French poet Charles Baudelaire opined that fashion wasn’t merely ornamental, it was a mirror reflecting the spirit of the age. This continues to be true today. In certain corners of the internet, the ideal man lifts weights, tracks macros and speaks in clipped imperatives. He dresses not for comfort but for the camera, squeezing into compression gear or tightly tailored suits. And, most important, he performs for the feed: the viewers he hopes will follow, the followers he hopes will buy (his coaching program, his supplements—link in bio!), and the godless algorithm that plucks people from obscurity and turns them into celebrities.

This is masculinity built for the scroll. Being an alpha male today is partly about adopting an aesthetic shaped by culture wars and online provocateurs. The shift isn’t just about fitness or fashion; it reflects a perennial search for meaning. Where previous generations found identity in work, war or religion, today’s masculine ideals are being forged in the churn of Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and X. In a society unmoored from traditional institutions, many men turn to self-styled gurus to answer the ancient question: What does a man look like?

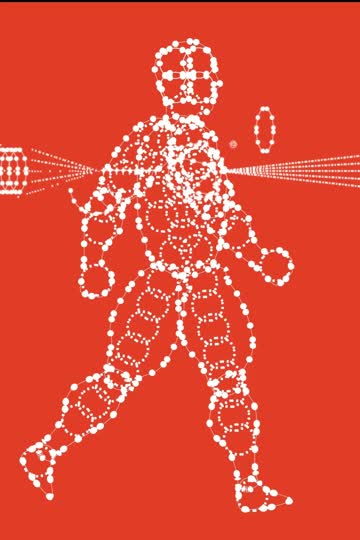

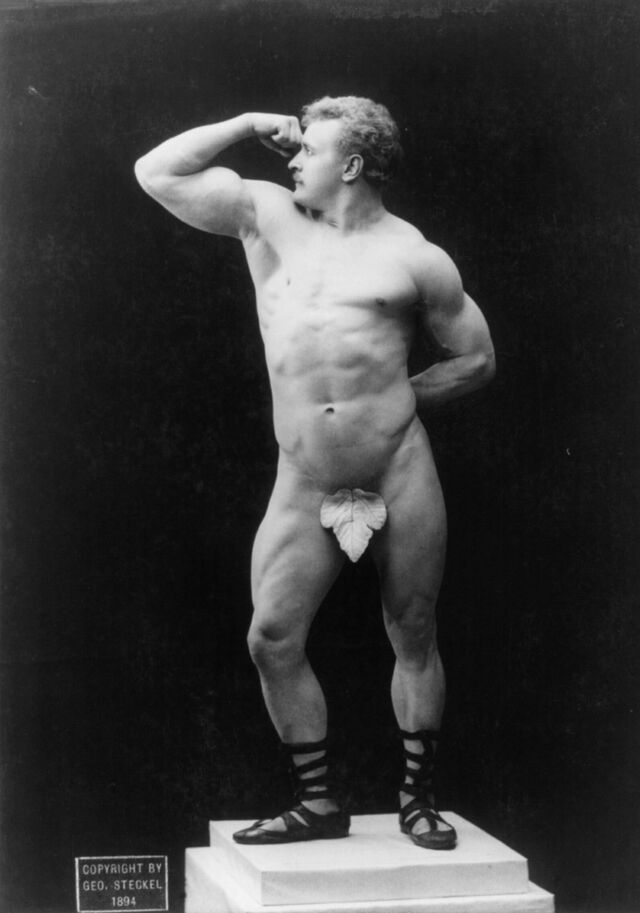

More than a century before influencers flexed for Instagram, there was Eugen Sandow, a 19th century German strongman once described as “the finest specimen of manhood.” He didn’t invent weight training, but he was the first to turn bodybuilding into a global celebrity brand.

Sandow gained attention by breaking strength-testing machines, but his fame didn’t explode until 1893, when Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. staged him as both marvel and metaphor. In one act, Sandow appeared onstage dressed as a British soldier fleeing a Boer assault. Trapped at a ravine, he lowered himself across the gap and allowed women and children to cross his broad, muscular back. The Boer Wars, fought between the British Empire and the independent Boer republics in South Africa, were fresh in the public imagination—bloody, humiliating conflicts that challenged the myth of British supremacy. As David Waller, one of Sandow’s biographers, put it: “It was designed to show quite literally how he could support the empire.” Sandow’s body, bending but unbroken, was allegory in muscle.

The mustachioed strongman toured Europe and the US, performing feats of strength in leopard skins and tight leotards. As his fame grew, Sandow tapped into an idea that would later become central to male self-improvement culture: branding. His name was stamped on dumbbells, cocoa powders marketed as early health tonics and a bestselling book, Strength and How to Obtain It. In 1897 the “father of bodybuilding” opened the Sandow Institute in London. It was a luxurious, three-story health club that offered private consultations and customized exercise plans. Many of his sales tactics—“act now” discounts, showing “before” and “after” photos, exaggerating medical benefits and appealing to science—continue to be used by modern fitness gurus.

Beauty standards are always shaped by cultural movements, which rest on the slow, grinding tectonics of politics and economics. The muscular male ideal we recognize today wasn’t always the pinnacle of male attractiveness. The ideal male beauty in the early 19th century was a gentleman, which is to say pale, slender and of romantic, melancholic demeanor. The upwardly mobile middle class—clerks, shopkeepers, office professionals—was more concerned with commerce than calisthenics, and visible muscle was considered the mark of a lowly field hand. “Very few upper-class ‘gentlemen’ would ever touch a barbell,” David Chapman wrote in Sandow the Magnificent. “It was too much like manual labor.” Sandow helped recast the male body as a site of ambition, reframing muscle not as brute force but as evidence of self-mastery. Strength, in Sandow’s world, was civilized and refined.

In postwar America, where Sandow’s heirs found their natural habitat in Southern California, muscle culture lost some of its respectability. During the late 1950s, Santa Monica’s Muscle Beach—a sunny stretch of sand that was once a family-friendly stage for gymnasts and acrobats—became dominated by bodybuilders, whose oiled torsos and theatrical poses drew mounting scrutiny. To many locals the beach took on a lurid edge; it was seen as a magnet for “sexual perverts” and, in more carefully whispered tones, homosexuals. In 1959 the city quietly shut it down. The lifters migrated south to Venice, where a small weightlifting pit known as the Pen offered them a new home. Venice lacked Santa Monica’s polish—it was grittier and more permissive, with tattoo parlors, smoke shops and roller skaters—but it became the spiritual center of American bodybuilding.

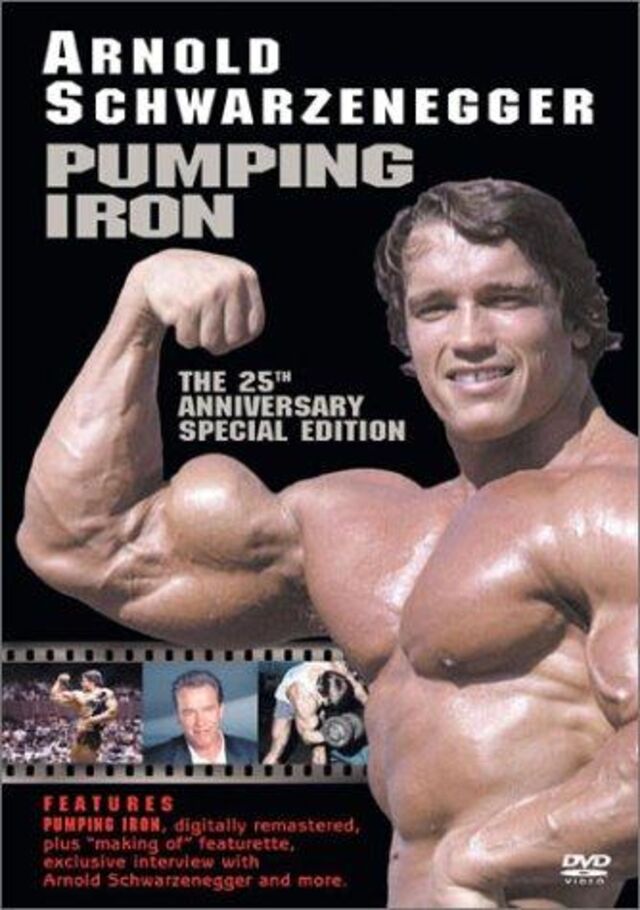

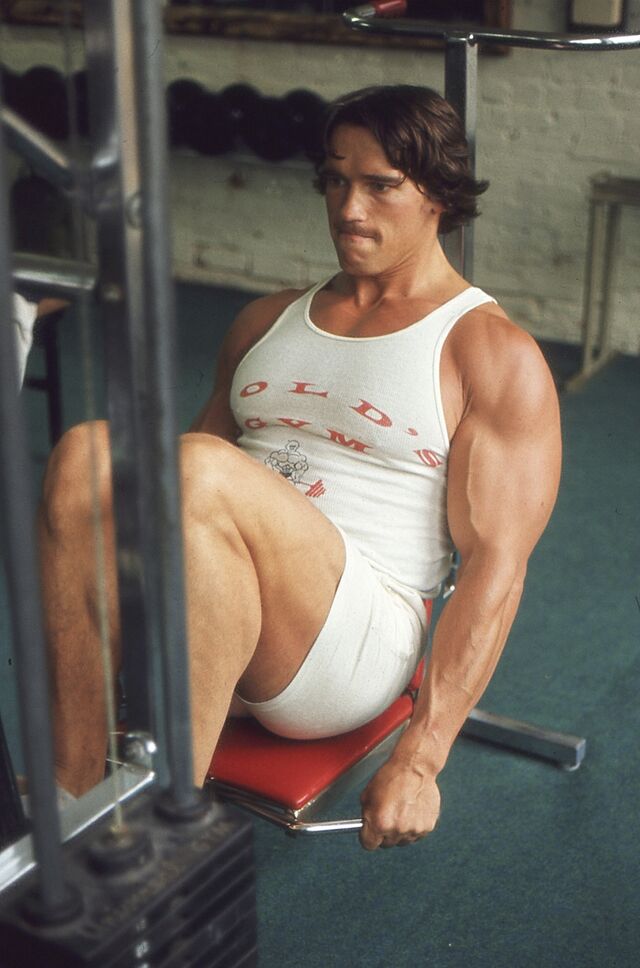

In the early 1970s, Ken Sprague purchased Gold’s Gym, a struggling fitness club just blocks from the Pen. Sprague believed it needed to be more than a training space—it had to be a theater. He organized competitions, invited photographers and let director George Butler use Gold’s as the set for his 1977 documentary, Pumping Iron. The film, which followed rising stars such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, became a surprise hit and helped legitimize a culture often written off as self-obsessed spectacle. Its success lured magazines and TV shows to latch on to the commercial fitness boom. By decade’s end, Gold’s Gym T-shirts—printed with a cartoon strongman inspired by Mr. Clean—were stretched across hulking torsos nationwide.

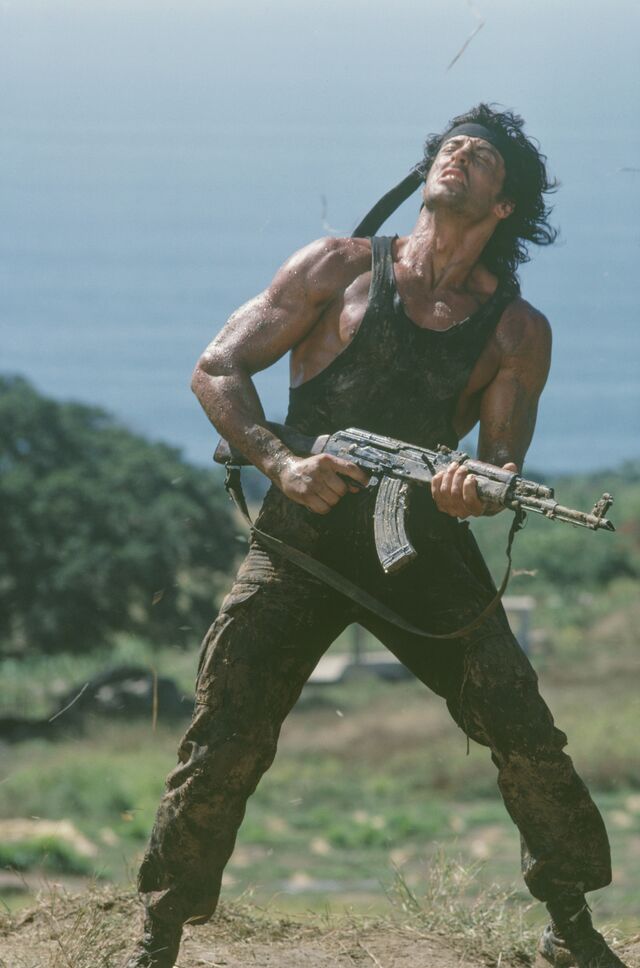

In the years that followed, Hollywood turned bodybuilders into icons. Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone dominated the box office with action hits such as Conan the Barbarian and the Rocky and Rambo series. They were cast as warriors and street fighters, and their physiques stood for grit, dominance and—at times—moral clarity. Their silhouettes became templates, reproduced in pop culture ephemera.

Even their attire began to echo their form. The 1980s power suit was a sharp departure from the soft-shouldered Brooks Brothers tailoring of old-money WASPs and the disheveled denim of countercultural hippies. What had once been flaunted in cotton tank tops now took shape in dark worsted wool: extended shoulder pads, inflated chests and waists tightened like lifting belts. Paired with a bright tie and contrast banker collar, the power suit embodied the “greed is good” ethos of a new tycoon class.

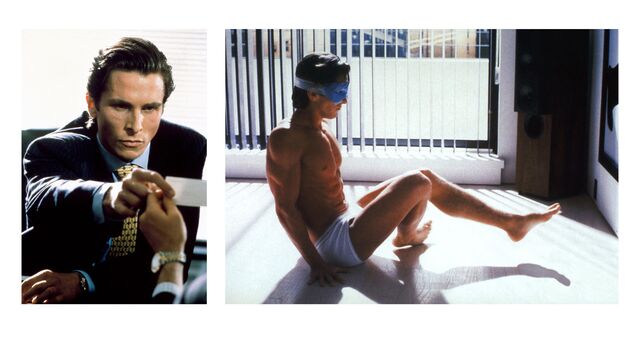

As the decade wore on, the line between discipline and vanity began to blur. No cultural figure captured that slippage more than Patrick Bateman, the status-obsessed antihero of American Psycho. Although the novel was published in 1991 and the film adaptation released in 2000, Bateman was unmistakably a creature of the ’80s. By day, he moved through Manhattan in Valentino Couture suits and Oliver Peoples glasses. By night, he peeled off his uniform to reveal a body maintained with crunches and skin-care routines.

In one of the film’s most iconic scenes, Bateman quietly unravels when a colleague slides over a newly printed business card—subtle off-white coloring, tastefully thick, watermarked. For Bateman the card is a stand-in for status, a way to measure self-worth in a room full of successful men. Style isn’t about his personal expression; it’s how he proves he’s the alpha.

Together, the gym body and the power suit formed a singular ideal: the optimized man. Whether he was lifting weights or managing capital, strength had become something to display, not merely possess. And yet, to be seen as dominant, a man had to conform to someone else’s idea of what dominance looked like.

The collapse of the dot-com bubble in 2000 ended the longest stretch of uninterrupted economic growth in American history. At the time, high fashion was still steeped in the austere minimalism of the 1990s—the Council of Fashion Designers of America had crowned Calvin Klein and Helmut Lang as Menswear Designer of the Year in 1999 and 2000, respectively. But as consumers tightened their belts, the fashion industry scrambled for ways to keep shoppers engaged.

To make old styles feel new, designers reshaped men’s silhouettes. In the early 2000s, Raf Simons, Hedi Slimane and Thom Browne rejected the bulky, broad-shouldered shapes associated with American tycoons, action stars and Armani swagger. They put the male wardrobe through a hot wash and tumble dry: Shirts tightened, jackets shrank, and trousers contracted in every direction. In the 2012 documentary 90s Anti-Fashion, Simons said he made clothes he and his friends wanted to wear because they didn’t see themselves in the “huge, suntanned, muscled Americano” that dominated fashion imagery. Slimane, reflecting on his adolescence, remembered being bullied in high school for having a slight build. They “were attempting to make me feel I was half a man because I was lean,” he told Yahoo Style in 2015. “There was certainly something homophobic and derogative about those remarks.”

Early adopters of slim-fit style were fashion-forward urbanites who embraced this European vision of youthful cool. They wore shrunken blazers, used chamomile-infused moisturizers and could explain the difference between Chelsea boots and jodhpurs. In search of a label for their aesthetic, the media landed on “metrosexual.” The metrosexual took pride in taste, but what set him apart was his attitude toward gender performance. As the New York Times wrote in 2003, this new archetype possessed “a carefree attitude toward the inevitable suspicion that a man who dresses well … is gay.”

While slim fit marched down high-fashion runways, it also crept into indie rock shows, early style blogs and online menswear spaces including Styleforum and Superfuture. These communities turned fit into a doctrine, elevating silhouettes like A.P.C. New Standard jeans and Band of Outsiders button-downs as markers of elite taste. As the Strokes played onstage in threadbare tees and skintight denim, wealthy urbanites chased the look by purchasing Slimane’s Dior 17cm and 19cm jeans, named after the width of their leg openings. Those priced out of luxury labels raided the women’s aisle, a gender-bending hack that Levi’s would later celebrate with its 2011 “Ex-Girlfriend Jeans” for men.

In its early years, slim fit was met with low-grade cultural panic. But soon everyone became a metrosexual. Fashion magazines treated slim fit as a kind of pseudoscience—any loose fabric signaled laziness or sloppiness. J.Crew helped bring this new silhouette into everyday offices. Its Liquor Store concept shop, opened in 2008, transformed an after-hours watering hole into a menswear-only boutique loaded with 1960s-era references to traditional masculinity—antique rugs, leather club chairs and Hemingway novels—even as it sold slim chambray shirts and cropped blazers. At the same time, Mad Men introduced a new masculine figure: Don Draper. Emotionally sealed off and impeccably dressed, Draper gave the slim-cut suit an edge of stoic authority. Shrunken clothes became synonymous with professional competence and upward mobility.

Slim fit’s early ties to gender rebellion faded as the silhouette was absorbed into more conventional ideas of masculinity. What once looked subversive became standard fare in offices, at weddings and on Tinder profiles. New subcultures rebranded the look with more conventionally masculine associations. EDC (everyday carry) enthusiasts, armed with pocket knives and multitools, adopted slim-fit gear as part of a rugged preparedness ethos. Their slim tactical pants and fitted henleys weren’t about gender ambiguity; they were survivalist uniforms. The rise of athleisure for men, particularly centered on slim joggers, pushed the same silhouette in poly-stretch fabrics, forming a softer kind of masculine armor. In Silicon Valley, tech founders embraced minimalist wardrobes built around Everlane tees, trim chinos and all-white sneakers. An aesthetic once dismissed as “metro” was now emblematic of self-optimization.

The slim-fit revolution, once a marker of fashion-forward rebellion, is now firmly mainstream. The early adopters have long since moved on to wardrobes built around Carhartt double-knee work pants, boxy hoodies and oversize tailoring. But beyond those circles, the pivot has been slower. For many—especially middle-aged men—slim fit still signals polish, effort and middle-class respectability (see Matt Walsh and Vivek Ramaswamy). It’s also the uniform of fitness influencers and grindset entrepreneurs, who populate a sprawling online ecosystem shaped by modern anxieties about masculinity.

The culture that produced these manfluencers emerged from a tangle of subcultures that took shape at the dawn of the metrosexual. The pickup artist scene, led by figures like Mystery and Neil Strauss, treated masculinity as a game: Confidence could be rehearsed, women were goals to be unlocked, and clothes were tools for climbing the socio-sexual hierarchy. In parallel, MMA fighters such as Georges St-Pierre and Chuck Liddell offered a new masculine ideal—not muscle for spectacle, but functional strength hardened through raw combat. On YouTube and in early fitness forums, ex-soldiers, bodybuilders and amateur life coaches used their physiques as proof of transformation. David Goggins, Zyzz and Jocko Willink—fitness guys who doubled as motivational speakers—cast the body as both weapon and wisdom. Hustle culture took these ideas further. Tim Ferriss, known for his 4-Hour self-help books, wrote about cold plunges and productivity hacks. Joe Rogan eventually became the connective tissue between these subcultures. His podcast empire fused fitness, supplements, self-help and libertarian suspicion into a single worldview—one-half gym science, one-half cultural resistance.

The Tate brothers took the raw material of that worldview and repackaged it with a harder ideological edge—blending fitness and hustle culture with anti-feminist backlash, nationalist grievance and a theatrical contempt for liberal norms. Not everyone in the alpha ecosystem shares their politics, but many embrace the same visual grammar. Ashton Hall, whose cold Saratoga water face plunge became a TikTok trend, uses similar imagery. Liver King followed a comparable formula, wrapping primal excess in a veneer of ancestral wisdom. Andy Frisella, creator of 75 Hard—a boot-camp-style program that promises toughness through discipline, dieting and discomfort—delivers YouTube sermons on sculpting abs and building wealth. These men may differ in tone, but they share an ideal: masculinity is under siege, and the only way forward is to optimize, aestheticize and dominate. For them, the body is a billboard for self-mastery, and slim-fit clothing is the wrapping that proves it.

This new wave of hypercurated masculinity is a backlash against a cultural landscape shaped by gender fluidity, body positivity and an ongoing renegotiation of gender roles. As celebrities like Harry Styles and Lil Nas X pose in dresses and blur the traditional lines between masculine and feminine, another current rushes in to reassert the old order. It pulls from earlier models: The mythic strength of Sandow, the beachside bravado of the Venice bodybuilders, the greed-soaked tailoring of 1980s finance and the tight-fitting clothes once labeled metrosexual. Today’s fixation on muscularity, discipline and traditional masculine aesthetics feels like a new chapter in that same historical cycle.

Where does this aesthetic go from here? When the cultural winds shift—as they always do—the alpha will update accordingly. The look will change. The slogans will too. But the performance will remain: a man offering a caricature as comfort, selling certainty to those unsettled by change.